In the winter of 2019, an elderly gentleman was admitted to our ward. His name was Mr. Ding, an aged man in his twilight years who had been living in a high-end nursing home for some time. During a brief interaction with me, despite my warm approach, he quickly stopped talking, closed his eyes, and remained silent. Mr. Ding had been hospitalized this time due to pneumonia and was receiving antibiotic infusions. His body temperature was normal, and his general condition was stable.

While reviewing his previous medical records, I discovered that two months earlier, Mr. Ding had been diagnosed with advanced liver cancer with multiple metastases. Considering his age and physical condition, his family and doctors had unanimously opted for palliative care to ease his pain. There was no documentation of his personal wishes in the records, leading me to assume he was unaware of the diagnosis.

The test results returned that day, showing improvement in the elderly gentleman’s infection but revealing abnormally elevated blood calcium levels. We confirmed that this was caused by lytic bone metastases resulting from the tumor. Administering zoledronic acid was identified as the simplest and most effective treatment. However, it was expected to cause side effects such as fever, muscle pain, and fatigue, though these discomforts typically subside within a few days.

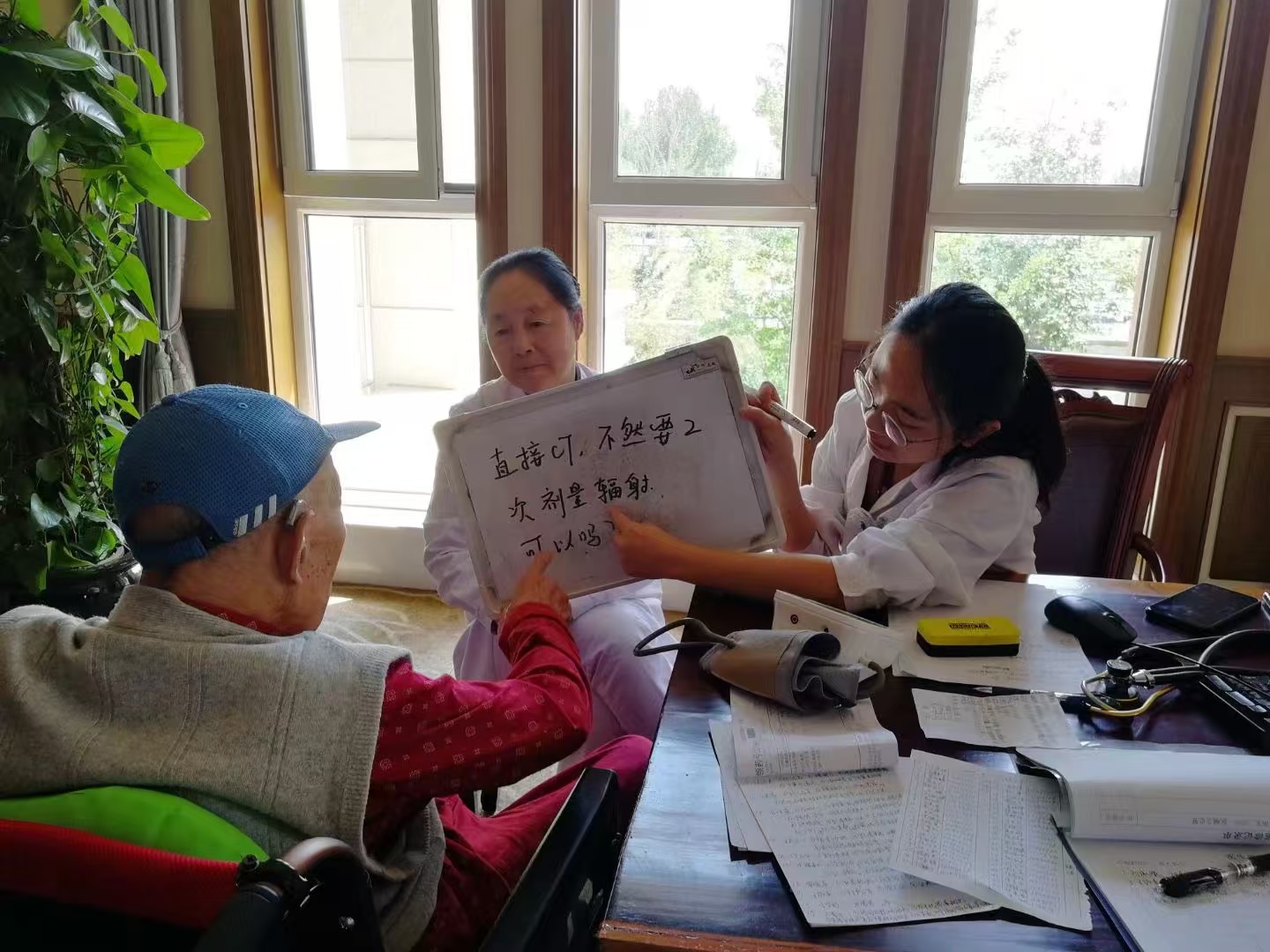

Mr. Ding had only one daughter, who visited daily to deliver meals and provide companionship. After obtaining his family's consent and explaining the treatment to Mr. Ding, we administered the infusion. As anticipated, he developed a fever the same day. For me, this was not concerning as it would not hinder his recovery from the lung infection. What I didn’t realize, however, was that this seemingly routine episode foreshadowed a turning point: Mr. Ding had learned of his condition and was preparing for the end.

The next evening, while on duty, the nurse informed me that Mr. Ding had refused to eat or drink for an entire day, despite repeated efforts by his daughter, son-in-law, and the staff to persuade him. Puzzled, I checked with the caregivers for any unusual incidents but found nothing. Determined to address the situation, I went to speak with him.

When I entered his room, Mr. Ding lay on his bed with his eyes closed. I gently called his name. He opened his eyes briefly, nodded at me, and then closed them again. After ensuring he was conscious, I asked if he was feeling unwell, but this time he waved his hand without opening his eyes. Bending closer, I asked softly, “Grandpa Ding, I heard you haven’t eaten much today. Is the food not to your liking? What would you like to eat?” He opened his eyes, looked at me, shook his head, and said, “No.”

Despite his resistance, I couldn’t let him continue his hunger strike. I tried reasoning with him, emphasizing the benefits of eating and the risks of excessive infusions. The nurse joined me in encouraging him, but Mr. Ding remained silent, his brow furrowed and his eyes closed. After more than ten minutes of fruitless persuasion, he finally opened his eyes and said, “Doctor, go tend to your other duties. Don’t worry about me.” Without waiting for my response, he turned his back to me, curled up under his quilt, and lay facing the window. Outside, the city lights glimmered, and traffic buzzed. Inside, Mr. Ding’s frail figure seemed to shrink further, isolating himself from the noisy world. I felt a pang of sadness but had no time to linger on my emotions. After confirming his vital signs and blood sugar levels were stable, I moved on to other patients.

By 9 p.m., my work was nearly finished, but I learned that Mr. Ding still hadn’t eaten or drunk anything. Suspecting underlying emotional distress, I decided to have a deeper conversation with him. Pulling a chair to his bedside, I began chatting casually. At first, it was mostly one-sided, with me asking about his family and hobbies. Gradually, my persistence broke through his silence, and he began responding with brief remarks. Over time, I learned that Mr. Ding had been an engineer. His wife had passed away nine years earlier, leaving him with one daughter who now had her own family. Independent and resilient, he had chosen to live in a nursing home to avoid burdening his daughter.

As our conversation deepened, he finally opened up about his thoughts. He revealed that he was aware of his cancer diagnosis. Although he had been asymptomatic and able to enjoy hobbies like calligraphy and reading, the recent fever made him feel death was imminent. He suspected the “side effects” were merely the doctors’ way of reassuring him. Yet, contrary to my earlier assumptions, his hunger strike wasn’t driven by fear of dying.

He explained that he felt his life had been fulfilling, his daughter was doing well, and he had no regrets. To him, the length of life no longer mattered; death represented a reunion with his late wife. He didn’t want to consume excessive medical resources prolonging what he viewed as inevitable. Moreover, he had chosen to come to the hospital rather than pass away at the nursing home to spare the other residents from distress. His refusal to eat was his way of accelerating the process, as he felt there was no meaningful difference between living a few more hours or days.

This was the first time I heard a patient express their true perspective on death. He was incredibly calm, and I was deeply shaken. Before this moment, whenever I faced patients, especially at that fleeting instant when I recorded their final ECG, I felt as if I were standing on the thin white line of "life," waving goodbye to them at death's threshold. They would dissipate into the dust of the universe, while I, despite giving my all, was left with a profound sense of guilt and defeat for failing to overcome death—burdened as I moved on to the next patient. Yet, I had never thought to ask them how they viewed death.

While I respected Mr. Ding’s perspective on death in its entirety, the rational side of me as a doctor told me that it wasn’t time to say goodbye just yet.So, I shared my thoughts with him. The fever caused by the medication was neither long-lasting nor overly painful, and it wouldn’t consume excessive resources. He could recover quickly and be discharged, still able to enjoy the peace of life. My words seemed to move him, and he fell silent. It was already late that night, so after saying goodbye, I got up and left. Later that evening, Mr. Ding resumed eating, starting with water and porridge. He recovered and was discharged shortly after, returning to his life at the nursing home.

A few months later, Mr. Ding’s health deteriorated as the tumor took its toll, and he entered his final days. He was admitted to the hospital again. By coincidence, it was during my shift that he passed away—silently and peacefully. Death had finally come, and I was the one to see him off from this world. Because I fully understood his thoughts and had done everything in my power to extend his life with dignity and quality, this time, I felt sadness, but also a profound sense of peace.

Department of General Practice, Nan Yan